The History of the Virtual School

A Historical Perspective Beyond the Pandemic

In recent years the COVID-19 pandemic put the virtual school into the global spotlight, leading many to assume that it was a product of the crisis. However, virtual schools - or online schools - have a much longer history. In this free piece, which includes links to subscriber content, I explore the evolution of the virtual school and debunk the notion that it emerged solely in response to the pandemic. There’s also a growing interest in the history of educational technology (Bates, 2023) and it is important to learn about it.

Virtual schools have a history that stretches back to the late 1980s. The foundation was laid decades ago and the current debate should focus not on whether it works - for the right students, it clearly does - but on how to encourage acceptance, widen access, and develop shared expertise in this model of learning.

Definitions

A virtual school is often synonymous with an online school (Bacsich, 2024). In some countries, such as the UK, the term may carry different meanings so we tend to use online school here in the UK. An online school refers to a school where the majority or entirety of teaching is conducted online through digital means, which may include digital networks and devices.

The main school for a child is where the majority of their education occurs and this could be supported by a supplemental school which provides a smaller portion of their education. A supplemental online school therefore refers to an online school where the child receives instruction in a limited area, such as a single A-Level subject, GCSE course, or vocational training.

Therefore by definition, an online school can support both full and part time pupils.

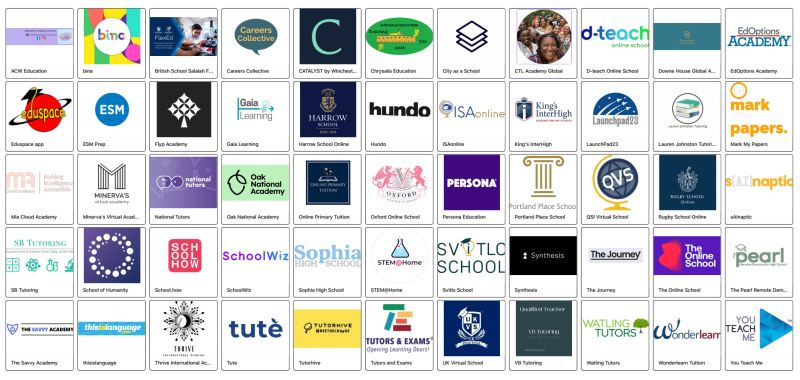

Last year I started to map them - predominantly for the UK - and publish it publicly.

So where to begin?

The Early Days: Laying the Foundation in the Late 1980s

The idea of a virtual school began to take shape in the late 1980s, long before the internet became an everyday tool. Pioneers like Morten Flate Paulsen, a Norwegian professor, were writing about the possibilities of virtual schools in his 1988 paper "In Search of a Virtual School.” He predicted that future distance education would eventually be dominated by the virtual school. At the time, distance education was mainly conducted through correspondence courses, with limited technology to support interaction between students and teachers.

Paulsen proposed that the future of distance education lay in creating an interactive, computer-based learning environment. He envisioned virtual schools as information systems capable of handling all the responsibilities of traditional schools, including professional, didactic, administrative, and social tasks, without the need for a physical site.

** Paulsen defines “a virtual school as an information system able to handle all the tasks of a school without the basis of an existing physical school.” I would suggest that virtual schools still need to develop stronger social components.

His vision marked the start of the shift from passive learning through mailed materials to active, dynamic online education facilitated by technology.

The Role of Technology: From Videotex to Computer Conferencing

During the 1980s and early 1990s, early forms of technology such as videotex and computer conferencing systems began to shape the landscape of virtual learning. Videotex, which allowed users to access text and graphics on their televisions via telephone lines, was used in countries like Austria and Sweden to deliver computer-assisted learning programmes. However, these systems lacked tools for interpersonal communication, a critical aspect of the learning experience.

It was computer conferencing systems, like EIES (Electronic Information Exchange System) and PARTICIPATE, that opened the door to the kind of interactive virtual learning we see today. These systems allowed pupils and teachers to communicate asynchronously, engaging in discussions, sharing resources, and providing feedback. In fact, by the mid-1980s, institutions like the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) and the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) were already experimenting with fully online courses, offering a glimpse into the potential of virtual schools.

Virtual Schooling in 2024: Proven Success for the Right Students

Fast forward to 2024, and UK virtual schooling is evolving into a diverse digital learning ecosystem which I wrote about in April for subscribers.

Integrating and Unveiling Nestedness in Digital Learning Ecosystems

Investigating the complex digital learning ecosystem, a pivotal question arises: How can we cultivate nestedness and integration within it?

Yet, despite its long history and proven success, much of the reporting surrounding online schools lacks this insight. Too often, the other question asked is: "Does online learning work?" when, in reality, the answer has been evident for decades.

For many students, especially those who enjoy self-directed, flexible environments, virtual learning can be a highly effective educational choice. Take this most recent example of a Ukrainian student who studied his A levels online and has gone on to secure a place at Southampton University to read Computer Science.

The success stories of online schools are evident around the world, with students excelling in remote regions without access to traditional schooling, to learners with unique needs who find virtual learning more supportive than traditional school or college. The pandemic did not create online learning; it simply highlighted its relevance and demonstrated its flexibility on a global scale.

Shifting the Debate: Access, Choice, and Collaboration

Given this long history, the debate around online education needs to shift. Instead of questioning its effectiveness, we should be asking how to expand access and ensure that it is recognised as a valid, mainstream educational option. The real issues lie in ensuring equitable access, integrating virtual learning into the broader educational system, and developing a collaborative approach to sharing expertise in online education.

Widening Access: Virtual schools must be accessible to all students, regardless of geographic location, socioeconomic status, or personal circumstances.

Acceptance as a Choice: Online education should not be seen as a lesser alternative to traditional schooling. It must be accepted as a valid choice for students who may not thrive in conventional settings, whether due to learning styles, personal needs, or logistical reasons. Mainstream acceptance of virtual learning can allow students to make educational choices that best suit their individual needs.

Development of Shared Expertise: Finally, the education sector needs to cultivate and share best practices in virtual learning. Education leaders, edtech, academics, and policymakers must work together to develop high-quality, evidence-based strategies for online education.

Conclusion

The future of education is not about choosing between virtual or in-person learning but about creating an ecosystem that offers multiple, equally viable paths to success. The history of virtual learning shows that it is not a recent invention but the result of decades of innovation and experimentation. For the right pupils, virtual schools have proven to work—what we need now is to ensure that they are accessible, accepted, and continue to develop through shared expertise.

By recognising the long-standing history of the virtual school, we can shift the conversation toward how best to integrate this model into the education system as a whole, ensuring that it serves the needs of all students and continues to evolve in step with technological advancements such as AI.

A thank you and an invitation

Thank you for taking the time to read this far. You can support my work by subscribing to receive future newsletters. If you know someone who would find this newsletter valuable, refer them.